About Japan, Secret Spots, To Sightsee

Goryo-shinko , a folk religious belief of avenging spirits

Religion in Japan has been diverse since ancient times. Although national strategy has forced many changes in the direction of belief, today the majority of the population are atheists rooted in Buddhism. Nevertheless, we live our daily lives without being aware of it, feeling the soul and power in everything we see, not only in the gods and Buddha, but also in nature and everyday tools. In this country, both good and bad things have a soul, and if we worship them carefully and treat them with sincerity, they will guide and help us.

The most characteristic of such a wide range of beliefs in Japan is the belief in Gryo-shinko: for more than 1,200 years, it was believed that bureaucrats who were politically ostracised (mainly in connection with succession to the throne) and died an unfortunate death would become vengeful spirits after death and bring misfortune. It may have simply been a natural disaster or an epidemic, but it was natural to assume that all sudden and unfortunate phenomena were possessed by the deceased.

Powerful people built shrines for their deceased rivals, worshipping them as gods and asking for forgiveness. The annual events to appease the grudge spirits became customary and became known as ‘Goryo-e’, and they soon became the object of local people’s devotion, with few people knowing that they were grudge spirits in the present day. Interestingly, the original talent of the spirits has been transformed into the benefits of the shrines, and many people visit them in order to benefit from their talents. For example, Tenmangu shrines (Tenjin-sama) throughout Japan are worshipped as gods of learning, but the deity, Sugawara no Michizane, was a politically ostracised grudge spirit. He was a very good scholar, and this is featured in the shrine’s benefits.

The grudge I feel most sympathetic towards is Prince Sawara, the younger brother of Emperor Kanmu, who laid the foundations of the present-day Kyoto in 794. He was a monk at Todaiji Temple when his elder brother Emperor Kanmu ascended to the throne, but was forced to return to the priesthood and became the Crown Prince.

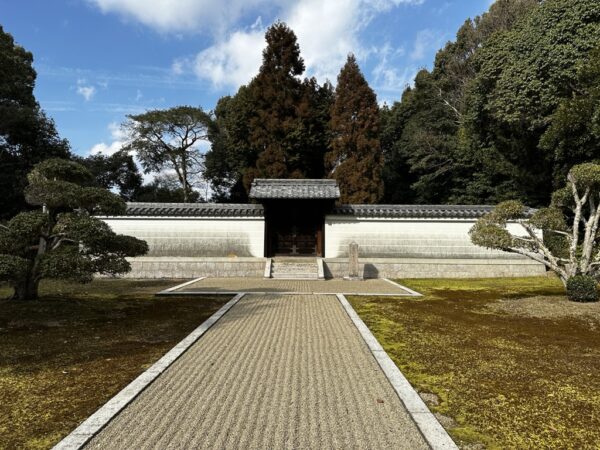

Later, however, Kanmu falsely accused his brother of a crime and exiled him, so that his son, not Prince Sawara, could take the throne. Prince Sawara died fasting on the way to the exile. Afterwards, Kannu’s family members fell ill one after another, and eventually Kanmu himself became ill. When told by a prayer master that he was possessed by Sawara, Emperor Kanmu had the body of his dead brother brought to Nara, where he had a mausoleum built and reburied. He also gave him the posthumous title of “Emperor Sudo” and enshrined him as an emperor. It is said that Kanmu moved the capital from Nara to Nagaokakyo and Kyoto, all to escape the haunting of Sawara.

There are many Goryo shrines in Nara and Kyoto that enshrine Emperor Sudō and other souls who died unfortunate deaths as political opponents during the Heian period.